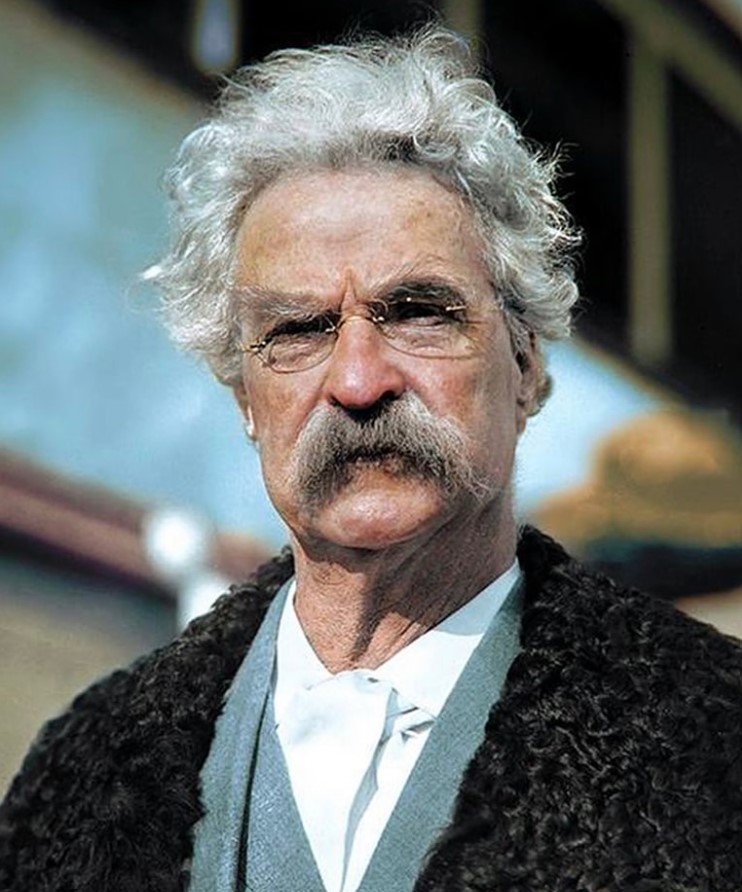

THE MARK Twain we learned about in school is a less than inspiring figure: Twain, the children’s author of riverside idylls; Twain, the bitter misanthrope who lashed out at society because of his personal failures; Twain, the racist who grew up in a slaveholding family.

Most famously, there is Mark Twain, father of American Literature–the figure consciously created by the American literary establishment in the 1940s and 1950s. This Twain is a powerful symbol of the American dream, the spirit of the frontier and westward expansion–he is a nationalist hero.

Yet Twain was one of the most forthright critics of American ruling-class ideology at the turn of the 20th century.

MARK TWAIN was born Samuel Langhorne Clemens in the slaveholding state of Missouri in 1835. He once wrote that slavery dehumanized the slave and made monsters of the slave owner. For much of his early adulthood, however, Clemens did not question the dominant ideas of his childhood.

Following the early death of his father, Sam Clemens had to earn money as soon as he could. His first paid work was as a printer’s apprentice. He spent four years in the mid-1850s working in various East Coast cities in horrible conditions and for practically no wages.

At the low point of his life, Clemens joined a militia fighting for the South, which was formed by his old friends from Hannibal. He deserted after three weeks and joined his brother in Nevada in 1861.

After a few wild years during which he tried (and failed at) silver prospecting, lived mostly on credit and consorted with the unconventional Bohemians, Clemens became a journalist. Although Clemens still held many of the prejudices of the day, while in Nevada and then California, he adopted a distinctive brand of social satire that championed the downtrodden and ridiculed the powerful.

He wrote a series of articles protesting discrimination against Chinese immigrants and exposing police brutality in San Francisco. “I have seen Chinamen abused and maltreated in all the mean, cowardly ways possible to the invention of a degraded nature,” he wrote in 1868, “but I never saw a Chinaman righted in a court of justice for wrongs thus done to him.”

After condemning the law’s double standard–he pointed out that the crimes of the wealthy go untouched, while the police brutalize the poor for the crime of being poor–Clemens was himself a victim of police harassment.

he died in 1910–Twain became an outspoken anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist. This era was one of extremes. The completion of the American Revolution with the end of slavery brought the promise of equality and democracy for all. But the same period saw the rise and consolidation of monopoly capitalism, vicious racism and divisions between rich and poor as great as any in Europe.

Mark Twain–anti-imperialist

AS U.S. industry expanded at a dizzying pace at the end of the 19th century, America was using its growing might to challenge its European rivals and conquer markets and territory abroad. In the process, it violated other peoples’ rights to independence and self-determination–the very values enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

For Twain, and many others at the time, Americas imperialist expansion violated the expectation that America would be different from the colonial powers of Europe. Twain explained in 1900 how he went from praising to condemning the “American Eagle”: